LiCoO2 might be the most famous battery material ever. With an impressive energy density and cycle life, it is hard to imagine there might be a better electrode material out there for lithium ion batteries. Many modern cathode materials are simply variations on this classic.

However, cobalt is somewhat of a tricky material to source. While there is plenty of it for now, cobalt is only found in a few places in the world. Cathode materials offering similar or better performance to layered cobalt oxide materials that use more abundant or easier to source metals may prove valuable to the battery economy.

Currently, simply replacing cobalt with another transition metal leads to some sort of compromise, either in electrochemical performance or long-term stability. Thus, new materials or new crystal structures that can facilitate the replacement of cobalt in battery cathodes need to be identified. This project seeks to investigate one such family of materials that may offer similar performance.

The idea is relatively simple. Change the coordination environment from octahedral to trigonal prismatic and see if these new layered transition metal oxides can offer similar performance to classic LiCoO2.

Trigonal prism coordination

While the classic LiCoO2 battery material has Co2+ ions in octahedral coordination environments, the materials studied here have trigonal prismatic coordination of the transition metals. Beyond this change in coordination, the structure still has a layered framework allowing for easy deintercalation of lithium ions, which are in an octahedral coordination environment.

The performance of this modified material is expected to be similar to classic LiCoO2, but perhaps a shift in coordination environment will bring other transition metals into a suitable redox range to be effective cathode materials.

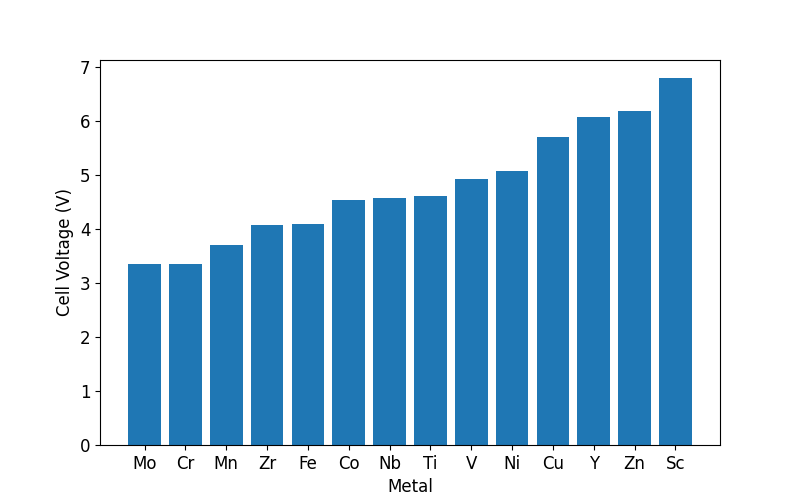

The metals we are going to look at here are all of the first row transition metals, plus yttrium, zirconium, niobium, and molybdenum. Other transition metals were excluded because they are either too expensive or too toxic.

Electrode Performance

Structures were fully relaxed for each transition metal and then single point energies were calculated for complete lithium removal. Battery performance was modeled considering the following reaction:

LiMO2 (s) → MO2 (s) + Li(s)

Of course, the lithium metal anode could be replaced with a graphite anode or other material for faster reaction rates or suppressed dendrite formation, but for the purposes of exploring new cathode materials, lithium metal serves as a suitable benchmark material.

As you can see from the plot above, all fourteen metals appear to have favorable cell voltages. Cobalt falls close to the middle of this voltage range, with a cell voltage close to that of the classic material with an octahedral coordination. Also, nickel is found to have a slightly higher cell voltage than cobalt, which mirrors results for octahedral materials.

Right next to cobalt on the plot above is niobium. LiNbO2 has been examined before both as a battery material and as a superconductor. Calculating reasonable cell voltages for LiCoO2 and LiNbO2 serves as a sanity check that the parameters used for this set of calculations yields reasonable results. Looking beyond niobium and nickel, copper and zinc are much cheaper than cobalt or nickel, and appear to have increased cell voltages relative to these standard materials. Lithium copper oxides have been synthesized in the past, and it may be worthwhile to try and prepare this material for experimental study. A promising lead!

Future Directions: Stability Analysis

These calculated cell voltages are really only the first clue in identifying a new cathode material. First and foremost, none of these calculations matter if no one can make the materials I dream up on a computer. Luckily, DFT can offer some insights into what leads might actually be dead ends before someone starts the costly materials synthesis and characterization process. These insights come in the form of stability or decomposition analysis.

In layered metal oxide battery materials, instability often comes from the low lithium side of the reaction. The most stable metal oxide framework that supports lithium insertion might not be the most stable metal oxide phase. If you take all the lithium out of our beautiful trigonal prismatic framework, it may decompose to another more stable metal oxide.

Calculations are underway looking at spinel phases and other common metal oxides to see how the trigonal prismatic structures considered here might fare in the real world. Stay tuned!

For reference, I would bill $1,500-2,000 for the work that went into this small project. If you would be interested in a similar investigation, send me an email at cascadecomputingllc@gmail.com

Leave a comment