Organic solar cells have been the subject of intense research for a few decades now, yet there are little to no commercial examples of this technology. Why? The ideal materials for capturing and converting energy from sunlight still remain elusive. This short project starts the development of a new active layer for organic solar cells, one that could be easier to commercialize than the current best-performing materials.

Why do we need new materials?

Organic solar cells have been around for a long time and a lot of really good absorbing materials already exist. Why search for new ones? The answer, in part, is because none of them have been good enough to commercialize. There’s a whole lot of conjugated polymers and small molecules that interact with light like crazy and make great organic solar cells on a research scale, but they just aren’t good enough for commercial applications. Rapid degradation and complicated or expensive synthetic routes are two of the biggest hindrances to commercialization of some of the most popular materials.

This mini-project seeks to try and develop a new absorbing material from a well-known starting place. Essentially, instead of trying to make already identified materials like PM6 more suitable for commercial application, what if there is a material that is already close enough that can be tweaked just a little bit?

Material Design Principles

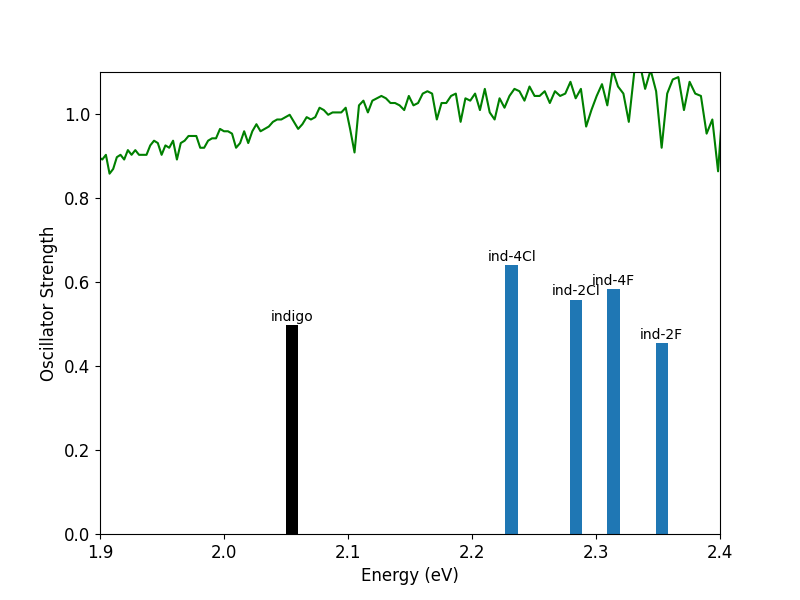

The first step in solar cell operation is harvesting energy from sunlight through absorption. An effective absorbing material needs to be able to capture as many photons as possible from the broadest chunk of the solar spectrum that it can. This translates to having a large transition dipole moment or oscillator strength (how strongly a material can interact with light or how easy it is to absorb a photon) and a transition energy or first excited state that lines up with an intense part of the solar spectrum.

Beyond absorption, organic solar cell materials need to have good crystal packings for large diffusion lengths and favorable orbital energies for charge transfer and collection. We will save consideration of these properties for future study, and just focus on absorption for now.

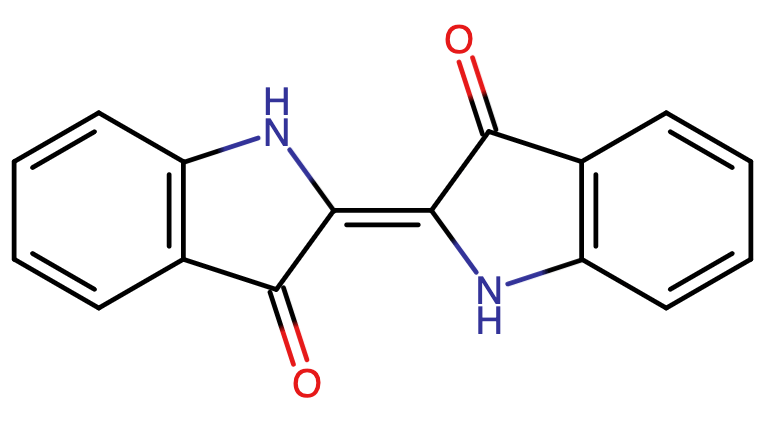

Indigo

Indigo already has several characteristics that make it a good starting material for optimization. First, it strongly interacts with light, which is what makes it such a good dye. And second, it is quite stable.

The benzene rings in indigo offer a ripe area for functionalization. Tweaking the pi system of electrons will affect the absorption properties of indigo, giving us a knob to turn to try and maximize energy harvesting from the solar spectrum.

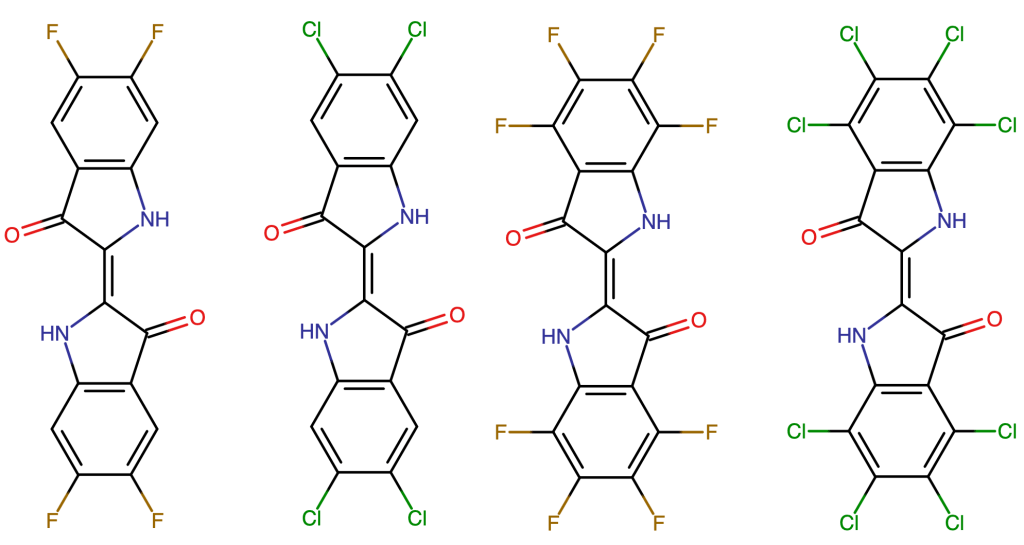

An almost limitless amount of derivatives of indigo can be imagined. This initial study focuses on seeing if halogenation with fluorine or chlorine can lead to better harvesting of the solar spectrum. Halogenation is only an entry point to chemical modification of indigo, and other derivatives may be considered in the future.

Shown above are the calculated first excited state energies and oscillator strengths for the range of indigo derivatives studied here. The solar spectrum is also shown above in green for reference. All of the halogenated derivatives are clustered higher in energy than unsubstituted indigo. The solar spectrum is indeed more intense around 2.2 – 2.4 eV, so shifting the absorption energy to this range may allow for the harvesting of more photons. Additionally, three of the halogenated derivatives have larger oscillator strengths, meaning these molecules will be able to absorb more light, another favorable characteristic identified above. At a first glance, it would appear that halogenating indigo may make it a more promising solar cell material.

Orbitals and Charge Transfer

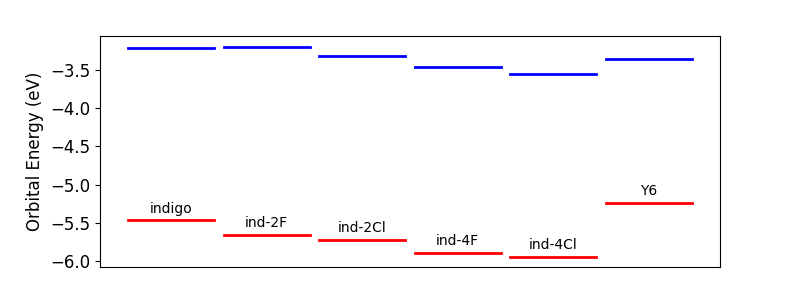

Absorption is only the first step in solar cell operation. Once an excited state is created in an active layer, the energy from this state must be harvested. In organic solar cells, this is achieved by separating the excited electron and hole through charge transfer to another material. One of the best electron acceptor materials out there is Y6 and while Y6 itself may be too synthetically complex to commercialize, it can serve as a useful reference material here.

To achieve efficient charge transfer to Y6, the frontier orbitals, especially the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (or LUMO) need to be close in energy. The plot above shows the energies of these frontier orbitals for indigo, its derivatives, and Y6. We see that halogenating indigo has the effect of lowering the LUMO in energy. Indigo on its own has a LUMO that is only slightly higher in energy than Y6, and chlorinating indigo brings the LUMO almost isoenergetic to Y6, which could drive faster charge transfer. So, the indigo-2Cl derivative may be able to absorb more light and undergo more efficient charge transfer to Y6 or a similar acceptor material. Promising!

Unfortunately, the more heavily halogenated derivatives have deeper and deeper LUMO levels, becoming lower in energy than Y6, which is likely to substantially slow charge transfer. While the indigo-4Cl and indigo-4F derivatives may be able to harvest more solar energy, they may not be as efficient in transferring that energy to an electron acceptor. Materials optimization is always a balance.

A good starting place

This short screening of indigo derivatives identified indigo-2Cl as a promising solar absorption material. Future work on this material will include simulation of molecular packing and charge transfer with Y6 and other electron accepting materials. Additionally, there are a plethora of other types of derivatives of indigo to consider, ones which may offer even stronger oscillator strengths. More rounds of screening could identify other promising leads.

For reference, I would bill $400-500 for the work that went into this small project. If you would be interested in a similar investigation, send me an email at cascadecomputingllc@gmail.com

Leave a comment